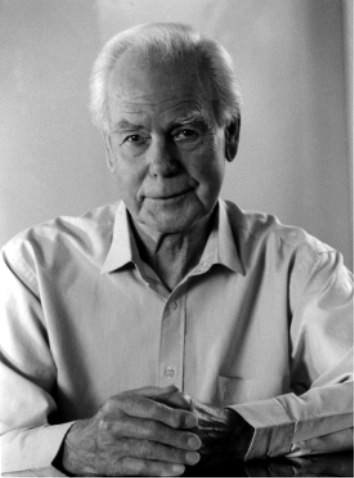

photo: Paul Watkins

IN MEMORIAM

DONALD MUNRO

M.B.E.

10.01.1913 - 18.01.2012

Baritone - Educator - Administrator

founding father of opera in New Zealand

and of

The New Zealand

Opera Company

recipient of the prestigious

New Zealand

ICON AWARD 2005

"I would like to tell you

that receiving this Icon Award, is the greatest thing that has happened in

my life.

For me, it is the greatest honour. I received a MBE in 1951,

but this Icon Award was awarded to me by my peers, not the politicians and

that says a lot."

Donald Munro, Arts Foundation Icon Awards, Wellington, 2005

Testimonials

from

Family, Friends and Colleagues

Meeting

Donald Munro

a reflection - Martin Cooke

In 1981 I had just begun my studies at the opera school of Sydney Conservatorium. Early in the course we had a master class and some young singers performing in a revival of the musical Oklahoma were invited to listen in. One singer was the very fine mezzo-soprano Kathryn Dineen from Adelaide who was about to join the Chorus of the Australian Opera Company. Kathryn also lived in Manly and we caught the Manly Ferry home together. As we alighted a most distinguished and very handsome man was there to pick her up. Donald at nearly 70 certainly stood out in the crowd and after sharing a few words together I knew he was someone special. Donald was born in 1913 and my late father was born in 1912. My father was tragically killed in 1970 and I think I was subconsciously deeply drawn to the fatherly figure of Donald Munro.

From that time onward we would often meet on the ferry or walking down the Corso and in the exchange of a few words I knew I was communicating with a most interesting, knowledgeable and wise man. Donald had me fascinated as a young man, I loved talking and listening to him and we got on very well.

Just before my graduation in 1983 I visited Donald at the Fairlight flat and sang for him. In one small session of a few minutes his appraisal and criticism were 100 % correct and I regretted that he had not been my teacher from the beginning. In 1984 Donald heard me sing the role of Jesus in the St John Passion and I remember his approval on that night gave me a much needed lift to my self-confidence. In 1985 I left for Germany.

Returning to Australia in 1988 after two and a half very tough years in Europe, I was guest soloist for the Colonial Day Concert of Manly Music Club which Donald attended and afterwards I asked him if I could study with him. Working with Donald for one year and for up to three lessons per week turned my singing career around totally. Donald helped me to regain my self-confidence and my love for singing.

He

was a demanding and very exact teacher; however with his gentle, direct and

constructive manner Donald could hit the literal nail on the head when he

worked with singers. He possessed the rare qualities of inspiring, motivating

and revealing the intricacies of the vocal art to the singer thereby enabling

the student to grasp basic concepts and implement necessary changes immediately.

Vaila Mead a friend and outstanding pianist gave me a tip in recognising the

hallmarks of an excellent pedagogue: if you haven’t made progress by

the 2nd lesson then change teachers. As a general principle there is much

truth in this statement and I have to say I did not need to look any further

when I think back to those first challenging and constructive lessons with

Donald Munro. We became good friends in 1988.

In 1989 Donald and Kathryn came to Europe to live in Bremerhaven where Kathryn

was engaged as a soloist at the Stadttheater and I returned to Munich. Within

a short time Donald had established a new vocal studio and professional singers

would visit him from Bremen, Berlin and Hamburg. An amazing achievement for

a man in his mid seventies in a new and foreign country: Donald simply made

an authentic and deep impression upon people. In Dec 1989 Sabine and I were

married; Donald came to our wedding and stayed with us. My new German family

warmed to Donald immediately and I felt as if I had a caring father at my

side on my wedding day and the beginning of this important new phase in my

life.

Donald Munro always believed in me and my abilities especially in those hard days in the mid-1980s. This helped me to persevere and I will be forever grateful for his support and friendship.

My

story is not unique, Donald Munro touched the lives of many people in a profound

way and I know he will remain in our hearts forever.

If any friends and former students of Donald would like to send me their reminiscences

I would love to post them on this memorial site. My email address is below.

Thank

you

Donald & Jilly

The Icon Awards give New Zealanders the

opportunity to identify those artists

who have excelled as contributors to the cultural identity of New Zealand

or represented New Zealand on the world stage.

The awards ceremony enables New Zealanders to thank the Icon Artists

for their contributions and to celebrate their achievements with them.

Reunion of the New Zealand Opera Company

Feb 5. 2007 in Wellington NZ

Donald Munro and Constance Scott Kirkcaldie were the guests of honour.

Mrs Scott Kirkcaldie was the long serving secretary and manager of NZOC

DONALD MUNRO

By

Doug Munro

Born in 1913, the son of British immigrants who met on the ship coming out, Donald Munro grew up on the family farm in the Otago township of Mosgiel and spent his out of school hours milking 19 cows morning and evening. His parents unwisely sold the farm and the family of six children moved to Dunedin in somewhat reduced circumstances. The depression hit home when Donald was still in his teens and he found himself grubbing for whatever work he could lay his hands on, be it office boy, waiting, labouring or gold mining. He also drove a taxis and trucks and, in his spare time, rode a motorbike with a recklessness that was talked about for years after. He was not very different from other young men who were a bit down on their luck in Depression-time New Zealand except that he went on to establish New Zealand's first and only national opera company.

What has not been mentioned is that he had a fine boy soprano voice and took singing lessons from his mother, an accomplished and versatile musician who described him as 'a little devil with the voice of an angel'.

The lessons resumed at about the age of 18 when his voice settled down and the talented young baritone was soon winning prizes in local competitions. His first stage role was as the Captain of the Archers in The Vagabond King in 1938. Then a visiting examiner from Trinity College, London, urged that Munro 'go home', as Britain was then called, to further his training. He sailed for England in 1939, arriving with 10 pounds in his pocket. The little boy from Mosgiel was on his way.

He enrolled at the Royal College of Music where he met my Scottish mother. In a scenario reminiscent of the depression in Otago, but this time in war-torn London, he took on musical work of an infinite variety to support himself. The original intention was to make his mark as a recitalist but in 1942 he joined Sadler's Wells Opera and so became involved in both disciplines. He also spent the two years 1946-47 in Paris studying under the baritone Pierre Bernac, to whom he acknowledges an enormous debt.

The 12 years in England and France were a great experience but Munro decided to return to New Zealand, partly for family reasons and partly at the prompting of Frederick Page who was then Professor of Music at Victoria University College. Arriving in Dunedin in 1951, he took over an established teaching practice of 54 students and soon learned that singing was one thing but teaching it quite another. There was no future for a professional singer in Dunedin and, again at Page's urging he moved to Wellington and slowly established another teaching practice and took whatever radio and concert performances that came his way. It was nevertheless a precarious living and it needed the second income of Jean Munro, an accomplished orchestral violist, to make ends meet.

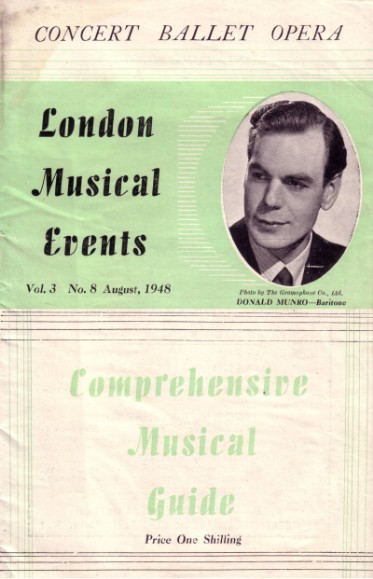

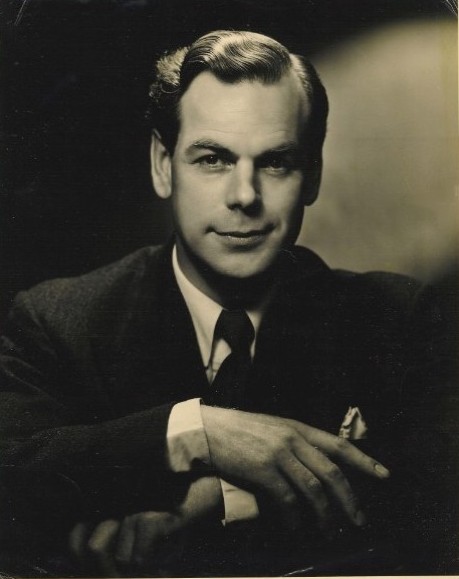

The Young Artist in London

He had no thoughts of getting into to opera until 1953 when asked by Layton Ring to sing in the Auckland Community Arts Service's production of Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona. It toured the North Island with such success that he decided to start his own opera company, which he did the following year with productions of La Serva Padrona and Menotti's The Telephone.

These were the humblest possible beginnings. Both operettas required a cast of two (one being a mute in La Serva Padrona), minimal sets and skeletal orchestral backing. But they still required money to mount and he worked in wool stores and abattoirs to finance these ventures. Many people candidly put it to him that he was mad to attempt the seemingly impossible, although many of these same people were to jump on the band wagon once it got going. Each year the Company mounted other productions, all paid out of Munro's pocket, each more ambitious than the last. With the staging of Menotti's Ahmal and the Night Visitors in 1956 and The Consul in 1957, the Company was performing three-act operas.

Menotti's The Medium 1955

In 1958, he announced that he would stage The Marriage of Figaro, and again his sanity was questioned. How are you going to cast it, even a shortened version, they asked? He double cast it and the following year a full performance of Figaro was staged. So within five years the Opera Company graduated from presenting operettas in the Concert Chamber in Wellington to performing a major three-act classical opera in the Opera House itself.

The New Zealand Opera Company's 1958

production of Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro

with (l-r) Honor McKellar as Cherubino,

Donald Munro as Count Almaviva and Beryl Dalley as Susanna

Much of this success can be put down to drive, flair and optimism. Many rallied to the cause, and for every doubter there was a stalwart ally. One ally was Raymond Boyce, who designed stage sets on a shoestring budget with little loss of quality; if anyone could fit a quart into a pint, Raymond could. Another was James Robertson, the conductor of the National Orchestra, who readily offered his services to the Company. A third was John Malcolm of the Department of Internal Affairs, who opened doors and gave limitless encouragement. Finding the right singers was Munro's particular talent. He adjudicated at singing competitions from Whangarei to Invercargill. As well as augmenting his income, he was ideally placed to spot talent. He was also instrumental in the formation of the support group, the New Zealand Opera Society. Another element in the equation was the co-operation with the two other cultural institutions formed around the same time - Richard Campion's New Zealand Players and Poul Gnatt's New Zealand Ballet Company. They readily loaned each other sets and props on a help-yourself-but-bring-it-back basis.

He couldn't afford the cost of storage for the Company's costumes and props so they were kept in his house, and my enduring childhood memory is a bedroom full of sets and costumes. I recall with yearning this enchanted aspect of my early life. Another presence in the Munro household was the boarder Graeme Gorton, who to this day is one of my father's closest friends. Originally one of his pupils in Dunedin, Graeme went on to become the Company's leading baritone. I also recall that my parents were open-handed entertainers and the normal household routine was frequently punctuated by small groups of musical friends who regaled themselves with laughter and drinks.

He built an opera company from the ground up with two objectives. Rather than perform just for city audiences, there was a conscious policy of taking opera to the people and this involved a rolling series of piano tours to even the remotest rural districts. The conditions in some of the country halls in which they performed had to be seen to be believed - but the show went on regardless. In those pre-television days it was the only cultural occasion for these small farming communities. As he reported in 1958: 'This year the Opera Company has played in 47 towns throughout New Zealand, to a total audience of 13,580 people. This excludes the Wellington season, where we played for six nights and a matinee to approximately 6,000 people. In all, the Company travelled approximately 4,000 miles. These figures reveal that we are really taking opera to the people and that the people themselves are really taking to opera'.

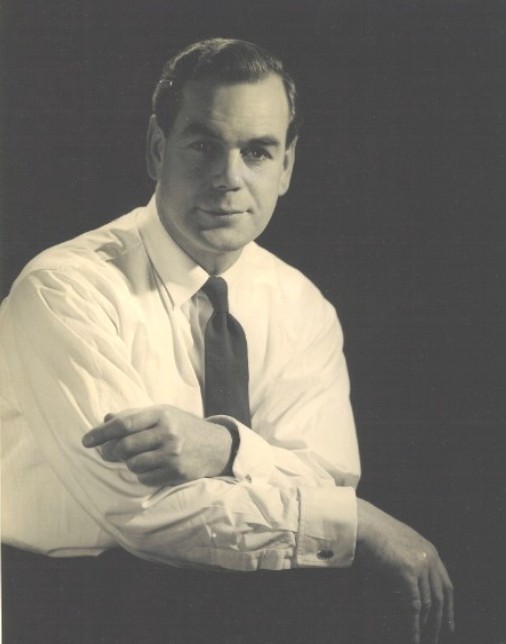

Donald Munro in 1951

The second objective was to provide employment for singers in New Zealand and thus stem the exodus of talent overseas. Munro paid his singers £20 a week, which wasn't a bad wage in those days. So successful was the Opera Company in retaining singers that it got to the stage when no one was applying for Government Singing Bursaries to go abroad. They had all they wanted in New Zealand and found a destiny at home, being paid to do the work they loved.

But as the Company grew, organisational changes were needed. Until 1958, Munro made all the decisions with the help of a small Board of Directors that included his wife Jean, John Malcolm, and the accountant Fred Burns. An expanded Board and a devolution of responsibility now seemed appropriate. In particular, he would bring in a businessman to look after the aspect of the Company's affairs, leaving him free to run the artistic side. Against the advice of many friends, his wife included, he chose Fred Turnovsky, a prominent Wellington businessman with a close involvement in the arts.

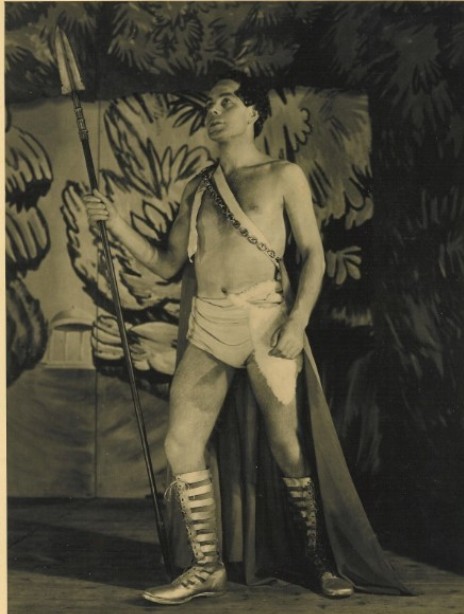

Donald Munro as Orfeo

in Orfeo and Euridice C.W.Gluck

Meanwhile Munro went to Glyndebourne on a Government Bursary to study opera production and management. During his absence three positive developments took place. One was the Government coming to the rescue with a financial package of £5,000 a year for the next five years. This saved the Company which had finally bitten off more than it could chew, from going into moth balls. Another was Turnovsky persuading New Zealand Breweries to be the Company's national sponsor. It was a tremendous coup that netted the Opera Company another £5,000 per year. This set the ball rolling and other commercial organisations soon waded in with sponsorships that bridged the difference between box office takings and expenditure. Constance Scott Kirkcaldie, the Secretary to the Board of Directors, took charge of that department and was highly successful in winking hard cash out of hard-nosed businessmen (just so long as she could get to the Managing Director and not be fobbed off by the Advertising Manager). The third development was the purchase of 76 Hill Street - a gracious house in Thorndon with an enormous rehearsal room - as the Opera Company's headquarters; it was purchased from the proceeds of a raffle organised by Phyllis Brusey, a new member of the Board. The Opera Company now had a home and a reasonably secure financial future.

But moves of a less pleasant character were also afoot. With the connivance of the new Board, Turnovsky installed himself as Chairman during Munro's absence and tried to get rid of him when he returned from Glyndebourne in late 1959. He got wind of the shenanigans and was offered support by Owen Jensen and Bruce Mason, who wrote columns for the two Wellington newspapers. When Turnovsky told him at the next Board meeting that his services were no longer required, he threatened to go to the press and the attempted coup d´état came to an abrupt halt. Turnovsky then offered him £3 per week, thinking that this would be knocked back, but the offer was accepted. Eventually he was appointed Artistic Director of the Company but hopes of a cordial working relationship based on mutual respect and a clear-cut division of authority were not to be.

For one thing, the Board intruded on the artistic side. Munro acknowledged that the artistic staff were responsible to the Board; but he also felt that there should be a clear separation of powers. The Board made a policy, set the budget and within these parameters the artistic should be left to get on with the job that only they could do. The artistic standard of the Company was, after all, their concern and they had knowledge and expertise which the Board conspicuously lacked. The Board, however, and the Chairman in particular, saw it another way and there were even occasions when the General Manager phoned the Chairman before making an artistic decision - which was to Munro not the way things should be done.

But that is the way they were. As a condition for coming onto the Board, Turnovsky demanded and got a 51 per cent controlling share in the Company, which he used to full effect. Energetic and domineering, Turnovsky exercised tight control over the Board and, through it, the Company. Munro always regretted that they could not work together harmoniously because their combined talents were formidable and could only have been to the good of the Company if synchronised. He gave up singing in 1962 to concentrate on the Artistic Directorship but found his talents and initiatives being stifled by directives from above.

Yet all seemed fine on the surface and the Company enjoyed spectacular growth and success. With the new sponsorship, grand operas were staged in majestic sequence, usually three a year, double billed and double cast. With a first-class ensemble of singers, mostly discovered and recruited by Munro, the standard was high. He was also awarded and MBE in 1960 for his services to opera. After ten years' existence, the Company had produced 19 operas, given 432 performances with orchestra, and over 1000 with piano, and had played to over half a million people. It is an impressive record, in which the shrewd business acumen of Fred Turnovsky played its part, but beneath the surface all was not well.

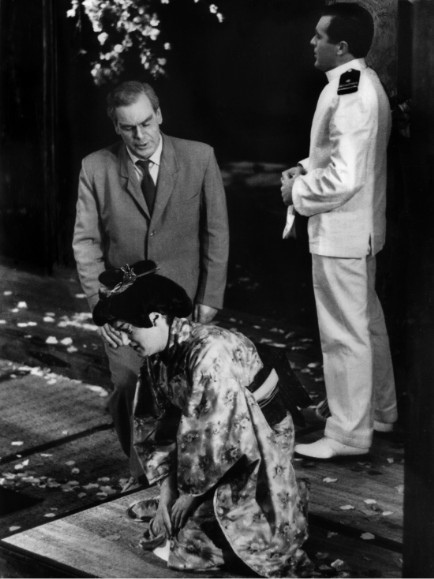

New Zealand Opera Company's 1960

production of Puccini's Madam Butterfly

with (l-r) Donald Munro as Sharpless, Dorothy Hitch as Suzuki and Jon Andrew

as Pinkerton

Although regaining his position on the Board as Artistic Director, Munro felt increasingly marginalised. The early 1960s were difficult years and got no better, not least because the Board kept demoting him in the hope of easing him out. Complicit in this was his old friend James Robertson, who returned to New Zealand in 1961 as conductor of the Concert Orchestra (which had just been formed to serve the needs of opera and ballet) and was invited back on to the Board as Musical Director. But far from being an ally, he was given the Artistic Directorship at his own request and Munro was then made Productions Manager. Thereafter, the Artistic and Musical Directorships were paired, thus tactically preventing him from regaining his old position as Artistic Director. (this lapse in loyalty on Robertson's part hurt Munro deeply but fortunately by the late 1970s the two had resumed their former close friendship). As if that wasn't enough, he was reduced to Opera Manager in 1965, another demeaning demotion. To a considerable extent, my parents were successful in shielding their children from what was going on, but inevitably we got an inkling of it - at least in broad thrust if not in exact detail.

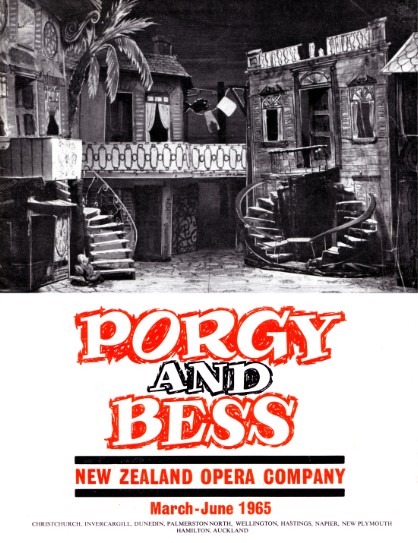

But there were high spots amidst the gloom. The 1962 production of Carmen with the stunning Joyce Blackham in the lead role was a runaway success.The Tosca of the year before was, in Munro's view, the Company's finest production ever. The biggest success, however, was the 1965 production of Porgy and Bess.

For the first time the Gershwin family permitted a non Africa-American cast. Inia Te Wiata was an unforgettable Porgy, and although three other principals were African-Americans, the remaining cast and chorus were Maori. It was a resounding artistic and box office success but the Company lost all of its takings and more on a long and disastrous Australian tour. Nevertheless, the tour was a turning point for Munro: it indirectly led to his sudden resignation from the Company and it positioned him to find alternative employment.

As Munro tells it, Turnovsky was causing ill-feeling between the Company and various other bodies, including the Ballet Trust, the Broadcasting Corporation and the Arts Council - in sad contrast to the co-operative spirit of the 1950s. Matters were getting out of hand. In response he wrote a letter from Australia, for tabling at the next Board meeting, to the effect that Turnovsky had become a liability to the company and he should resign the Chairmanship in order that the damaging rift with the other bodies might be mended. The letter was duly tabled some weeks later. Meanwhile, Turnovsky had lobbied and when the crunch came the other Board members unanimously supported him. In response, Munro took a piece of paper from the table and wrote out his resignation there and then.

The New Zealand Opera Company's 1961 production

of Donizetti's Don Pasquale

with Donald Munro as Malatesta and Mary O'Brien as Norina.

Many consider Munro to have been a 'natural' Count in The Marriage of Figaro,

but he rates more highly his performances of Malatesta.

Although out of work, he had the satisfaction that it took two-and-a-half new positions to fill his shoes and the Company even temporarily reinstated him for the Christchurch production of Die Fledermaus to get them out of the mess they were in. It was but a temporary respite and he planned, if all else failed, to buy a friend's corner shop just down the road from his home in Hataitai. This would not have worked and fortunately it never came to that. The irony is that had Munro chosen to start up a new opera company he would have taken every New Zealand Opera Company singer with him, such was their personal loyalty.

What happened instead also flowed from

the Australian tour of Porgy and Bess.

During the Adelaide stop-over he was invited to apply, successfully in the

event, for a position to teach singing and direct opera at the University

of Adelaide's Elder Conservatorium of Music. He was 54 when he took

up the appointment in early 1967 and the family made a somewhat difficult

transition to life in South Australia. Munro eventually became Dean of Music

at the university, a position he held until his retirement in 1978, some 12

years after arriving in Adelaide, or just a year short of his tenure with

the Opera Company. He also sat on various Sate and Commonwealth Government

arts funding bodies. After the break-up of his marriage in 1982 he moved to

Sydney where he maintains a teaching practice. He visits New Zealand fairly

frequently and keeps in close touch with friends from Opera Company days.

His parting shot when resigning from the Opera Company was to tell the assembled Directors that his creation would last another four years under their stewardship. He derived no pleasure when his prophecy was fulfilled, although the Board was not entirely to blame. There were other considerations in the figurative balance sheet. The Company had exacted a heavy financial, physical and emotional toll. He often reproached himself for touring so much when his family needed him at home, and my mother deserves a medal for coping with fractious children during their father's frequent absences. After the demise of the Company he occasionally felt that he had wasted years of his life in an ultimately futile endeavour and he once said to me about the Adelaide job: 'it all came too late'.

But there is another way of looking at it. Out of nothing he created a truly national institution of high artistic merit. The Company took 37 different operas to the people, whether in the cities, provincial centres or rural areas. Beginning with The Telephone in 1954, it swan-songed with Aida in 1971. In doing this, the Company raised operatic consciousness throughout the country and gave pleasure to untold thousands. Apart from the National Orchestra, the New Zealand Opera Company must go down as the country's most significant cultural entity. Not leas, it nurtured resident singers, gave them full time employment, the opportunity to develop professionally at home, and the Company was soon attracting back those who had gone overseas beforehand. Such were its standards and quality of training that when Noel Mangin, Peter Baillie, Jon Andrew, Mary O'Brien and Lynn Cantlon ventured abroad, they had little difficulty in launching successful careers in Europe and North America.

Our regret has to be that Munro was prevented from fully realising his vision. He founded and developed what has been described as the most exciting artistic venture in all New Zealand's history. Ironically, he attracted singers back to New Zealand but was ultimately compelled to see out his own career overseas.

The Foundation Years

of the

New Zealand Opera Company

1954-1957

By

Doug Munro

During 1975, the Settlement Restaurant in Wellington featured Sunday night

concerts to attract extra custom. Looking for something different, the management

arranged for a staging of Mozart's Bastien and Bastienne. It was, by all accounts,

a memorable performance of an attractive operetta about young lovers being

reconciled.(1) Written when Mozart was

a mere twelve-year-old, this 'agreeable trifle', in the words of one opera

analyst, 'is very suitable for puppet theatres…',(2)

and evidently also for restaurants. The staging of Bastien and Bastienne at

the Settlement Restaurant may have seemed an original idea, but it had been

premiered in New Zealand almost twenty years earlier, in 1956, by Donald Munro's

fledgling New Zealand Opera Company (henceforth the Opera Company). The Opera

Company went on to become a dominant feature of New Zealand's cultural landscape.

There were other opera groups in New Zealand during the 1950s and 1960s but

none were professional, except for the Opera Company. It was, moreover, a

touring company which took opera to the people, from one end of the country

to the other. While several other opera groups have had books written about

them, the Opera Company's story remains to be told in any detail. (3)

Donald Munro is my father and the early years of the Opera Company, which

saw the transformation from 'agreeable trifles' to grand opera, roughly coincided

with my boyhood. How does one go about writing of one's parent? Ashley Brilliant

has made the not-so-facetious remark that 'Every family should have a historian,

to make sure that the record gets properly falsified'.

(4)

Instead, I prefer Bruce Mason, who commenced his one-man play The End of the Golden Weather with an invitation 'to join me in a voyage into the past to that territory of the heart we call childhood'. (5) In similar fashion, readers are invited to listen to a historian reminiscing on a childhood where a constant household presence - almost a sibling - was a fledgling opera company. But memory can be a dangerous thing and the enemy of accuracy; and the skeptic might say that checking my memory against that of my 92-year-old father is to multiply the hazards. These risks are real enough so I have run for the cover of archives and taken recourse in the contemporary written record.(6)

Donald Munro aged 48

Born in Mosgiel in 1913, and encouraged to sing by a highly-musical mother,

my father emerged as a lyric baritone. He went to the Royal College of Music

in London in 1939 and in his studies culminated in winning Tagore Gold Medal

for the best student. He married a Scottish violin student at the College,

Jean McCartney, and my mother went on to play in the Jacques Orchestra while

my father sang with Sadlers Wells and the Old Vic, performed lieder recitals

at Wigmore Hall, did broadcasting on the BBC Third Programme, and spent two

years in Paris under the tuition of Pierre Bernac. Two sons came along, myself

in 1947 and Ian in 1949, and were enrolled at a prep school whose fees were

beyond my parents' reach. Freddie Page, the Professor of Music at Victoria

University College, was visiting London and urged my father to return. 'New

Zealand needs you, Donald', said Page, with the assurance that there would

be plenty of work. Arriving in Auckland in May 1951, aged 38, my father told

a reporter on the wharf, 'Yes, it was a big decision, but things aren't the

best in England, and I'm prepared to sacrifice a lot to see that my two young

sons get a chance. That's my real reason for returning - and staying'. (7)

'New Zealand certainly needed Donald', a friend remarked, 'but I could have

told him that there would be very little work.'(8)

Rejoined by the family a year later and settling in Wellington, my father

took what work was available. He was in demand for oratorios.

(9) He got broadcasting assignments, talks as

well as singing. He travelled to other centres for recitals organized by the

British Music Society. He also took singing pupils at home whom my brother

Ian mimicked with such cruel accuracy from the other side of the door that

my father had to hire a studio - in Lambton Quay where we saw the Queen and

the Duke of Edinburgh's stately procession through town on the 1954 royal

tour. But whatever the variety of work there was never enough of it and it

never paid enough. The prevailing attitude was that singing ought to be done

for nothing because it wasn't worth paying for. As a result, the family was

perpetually hard up and definitely needed the modest second income brought

in by my mother, who was principal viola in the Alex Lindsay String Orchestra.

(10) To this day my parents have rather

grim memories of the 1950s in that cold rented house in Karori and the somewhat

patronising neighbours (with one exception), all of whom owned their own homes.

My own memories are of a different order. I would sit by one of the large

radio speakers in the living room, much like the little dog in the HMV logo,

listening to my father's radio broadcasts and hanging on every note, and I

was always disappointed if not allowed to go along to his studio while he

rehearsed.

The turning point professionally, but not financially, came in mid-1953 when

my father sang at the Auckland Festival in Menotti's operetta The Telephone.

That was followed by taking the part of Uberto in the Auckland Community Arts

Service's production of Pergolesi's intermezzo opera La Serva Padrona.

(11) The thought of starting an opera

company had not entered his head to that point but such was the spontaneous

audience enthusiasm towards the latter's tour of the North Island, from Kataia

to Wellington, that he saw this as a way to make a living. Back in Wellington,

his intention to start his own opera group was greeted with an uproar of disapproval

and derision. 'Who does he think he is?' was one response, and a number of

people made rather abusive phone calls, a Dunedin acquaintance telling him

that he was 'a silly man with his head in the clouds'.

Table 1:

Productions, 1954-1957

1954

The Telephone - Menotti

La Serva Padrona - Pergolesi

1955

†The

Medium - Menotti

The Telephone - Menotti

†Susanna's Secret - Wolf-Ferarri

1956

†Amahl

and the Night Visitors Menotti

†The Impresario - Mozart

†*Bastienne

and Bastienne - Mozart

1957

†The Consul Menotti

† New Zealand premiere

* Bastienne and Bastienne was not performed at

any

major centre but toured rural districts to piano

accompaniment.

Donald

Munro as Colah

in Bastien and Bastienne in 1956

He went ahead regardless and in October 1954 the New Zealand Opera Group,

as it was initially called, opened its first season with La Serva Padrona

and The Telephone, under the auspices of the Wellington CAS (see Table 1).

There were three nights in Wellington and a further night at Lower Hutt, the

admission charges being 7 shillings and 6 pence and 5 shillings. There were

also lunch hour performances of The Telephone for two shillings entry, which

went a long way towards paying for the hire of the Concert Chamber. My father's

decision to mount two opera buffa in which he had sung the year before was

purely practical: he had done it before, knew what to do, and could do it

with the same people. In this way soprano Mary Langford and pianist David

Galbraith, who had been involved in the 1953 La Serva Padrona, came down from

Auckland, glad to get work, and were put up in the Munro household. Equally

important, the modest nature of the venture made it affordable, an important

point since my father was financing it from his own pocket. The two one-act

operettas with a cast of two required few stage props and a small orchestral

backing. (Actually, La Serva Padrona has a cast of three but Vespone, the

valet, is a mute and Galbraith acted the part.) What may sound simple and

straightforward was anything but. Period costumes had to be obtained for La

Serva Padrona. Some of the stage props were borrowed but other had to be made

(and my father sang the opening night with his hands coloured red, having

painted the telephone box only twenty minutes earlier). Singers, stage crew

and orchestra had to be paid. The Concert Chamber had to be hired. There was

also competition for bums on seats.

It is a misapprehension that New Zealand in the 1950s was a cultural wilderness

of beer, rugby and racing. Before and during and directly after the Opera

Company's first season, Wellington audiences had any amount of 'high' entertainment.

Edith Sitwell and Lewis Casson gave recitals of poetry and drama, the Wellington

choral group Schola Cantorium performed in the Town Hall, and the tenor Johnny

Ambrose gave recitals in a city church. Stage performances were mounted by

the locally-based School of Russian Classical Ballet (Coppelia), the Wellington

Technical College Old Students' Light Opera Group (Miss Hook of Holland) and

the Wellington Repertory Theatre (Lady Windemere's Fan). The annual Wellington

Primary Schools Music Festival (in which I sang and played the tenor recorder

in 1958 and 1960) was performed the week before and the Opera Company's lunch

hour performances of The Telephone in the Concert Chamber clashed with National

Orchestra performances in the contiguous Town Hall. This saturation helps

explain why the Opera Company's initial season was not performed to full houses

despite newspaper critics hailing the opening night as a 'sparkling debut'

that comprised 'some of the brightest, breeziest musical entertainment we've

had around the place for a long time'. (12)

It is one thing to receive critical acclaim. It is another thing to balance

the books in the face of sparse audiences. But it was a start and a reservoir

of goodwill was evident. Geoffrey Newson, who played the double bass, refused

to accept his wages. He banked his payment cheque but sent my father a personal

cheque of equal value with a covering letter that ended: 'Knowing the difficulties

that beset you in setting out on such a venture, so worthwhile artistically

yet so lunatic to the hard world of commerce, I would like you to accept the

enclosed contribution towards your plans for next year with all good wishes'.

(13) Others besides Newson thought that

the Opera Company was 'most commendable and deserving of every encouragement'.

James Robertson, the conductor of the National Orchestra, readily lent his

services; he became the Opera Company's Musical Director, joining a small

Board of Directors. Help came from other quarters. The composer Douglas Lilburn

loaned my father his Morris Minor for Opera Company business, which was a

godsend, saving him hours of travel time around Wellington. (14)

Lilburn also gave the penurious Munros the use of his bach at Paekakariki

for a Christmas holiday, which I ruined by getting very severely sunburned.

The following year the cellist and music critic Russell Bond loaned the family

his bach at Raumati South for another Christmas holiday.

In an inglorious encore I badly stubbed my toe and had a frightful nightmare. The doctor was called and he said to my father, 'The boy's alright. It's you I'm worried about'. My father had been working long hours at the abattoir at Ngauranga Gorge and Dalgety's wool store at the end of Thorndon Quay in order to put bread on the table and to finance his next productions. He organized and sang in another season of opera and not surprisingly had become very run down. At the same time, incidentally, Poul Gnatt was starting up the New Zealand Ballet Company and he financed his own grand passion by driving taxis.

Crucial to the early years of the Opera Company was a measure of assistance

from the Department of Internal Affairs. My father went to the Department

seeking financial assistance and was ushered into the office of one John Malcolm,

who gave his total support, and advised on how to best to apply for a grant.

He was soon a lifelong family friend and he too joined the Board of Directors.

In the event, the Opera Company received a guarantee from the Department of

£250 to cover its opening season (although most of it went to the Council

of Adult Education). Over the next three years the Opera Company relieved

further grants totaling almost £2500, which helped bridge the gap between

audience receipts and production expenses (see Table 2). Other ways of raising

money were the broadcasts of the operas for the YC radio stations and follow-on

recitals of opera music.

The Opera Company also toured throughout New Zealand, taking opera to the remotest rural locations. These piano tours, were an exhausting business, hard on the body and tough on the voice. But they helped make ends meet as well as providing work and experience for the singers. In 1955 a support group, the New Zealand Opera Society, was founded, which helped with fundraising as well as providing moral support. (15) But very little of the Opera Company's revenues went to my father as wages. The matter was raised at a Board meeting in January 1956 but a decision was deferred. It was realized that he ought to be paid but where was the money coming from? Even then, in 1957 a Board member resigned in protest when it was voted that some of the Internal Affairs grant be used to pay my father £8 per week for the next six months (i.e. £208). The following year he was paid £100 for past services and a salary of £100 p.a., which was still not much to live on. Again, my mother's income was critical to the family fortunes, if that is the correct word.

Table 2:

Public funding of New Zealand Opera Company, 1954-1957

1954

grant to CAS to assist forthcoming tour - £200

for initial cost of properties, costumes and mountings - £50

1955

grant to CAS to assist forthcoming tour - £200

half of surplus of tour to Donald Munro - £31. 9s. 3d.

grant to New Zealand Opera Company - £300

1956

grant to New Zealand Opera Company - £500

1957

grant

to New Zealand Opera Company - £500

grant to meet Opera Company's losses on The Consul - £700

TOTAL

= £2481. 9s. 3d.

source:

IA W2587, 155/206/729, Archives New Zealand

Finances, then, were the constant bugbear. My father started the Opera Company

to contribute to New Zealand's cultural life and to give himself gainful employment.

But the pickings were lean. He took what broadcasts and recitals that came

his way and in the 1955 Auckland Festival he sang the part of John the Butcher

in Vaughan Williams' romantic ballad opera Hugh the Drover. He was also in

demand as an adjudicator at singing competitions, which brought in more money

and, crucially, enabled him to find singers for various roles. The adjudicating

also meant that he was routinely absent from home during school holidays and

this, combined with touring, meant frequent absences from the family hearth

and my mother having to cope with two fractious boys. But my father's main

income at the time came from the abattoir and the wool shed.

It was death to the soul but unavoidable if the next season was to eventuate, which it did in September 1955 with the triple billing of The Medium, The Telephone (both by Menotti) and Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona. The Medium put the Opera Company on the map - such a dramatic opera, so well done, and Bertha Rawlinson in the role of the fraudulent Madam Flora so memorable. All the same, the smaller productions should not be under estimated. The two singing parts in both La Serva Padrona and Susana's Secret are demanding enough; and for The Telephone to succeed, the diction and timing have to be spot-on. Again, it was a case of putting up people and the household itself became something of a workshop. My bedroom became a storeroom for props, make-up and costumes, and some of my happier childhood memories are reading in bed surrounded by those accoutrements and dressing up in the costumes and putting on the make-up. I was photographed in Vespone's costume, sword in hand, and the photograph was used for the family's 1957 Christmas card.

By then, the foundations had been laid and the achievement was summed up by

a Listener reporter: 'To talk about New Zealand opera five years ago was like

speaking of world peace - it did not exist. Yet today we have a flourishing

opera company. It is a group without a permanent home, a group that assembles

for each production or tour and then disperses, its musicians and conductor

returning to the National Orchestra and its singers to towns all over New

Zealand, where they carry on their teaching or everyday work, but it is alive

and struggling, and presenting audiences with a new kind of entertainment

- the chamber opera'. (16)

The Opera Company's growth and forward progress were the themes of its foundation

years. The edifice was put together little by little, brick by brick. Each

year involved a more ambitious season. What started in 1954 with two opera

buffa in the Wellington Concert Chamber had progressed by 1957 to three act

grand opera with the staging of Menotti's The Consul in the Wellington

Opera House. These early years have been called 'the Menotti era', and my

father has often been asked why he chose contemporary operas by an Italian-American

composer as the Company's initial mainstay. The answer is simple. In 1948,

The Telephone and The Medium were running in London. Following the

departure of his American singers, Menotti auditioned my father and gave him

the leading male roles, but the season was unexpectedly terminated just before

he was scheduled to perform. Nonetheless my father realized that Menotti's

opera's were both musical and dramatic and thus likely to have broad popular

appeal, despite being an unknown quantity to New Zealanders. On this unconventional

basis the Opera Company was able to move into the conventional classical repertoire

in 1958 with Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro.

My father's objective was to place professional opera in New Zealand on a

permanent footing and to perform opera to a high standard using local singers.

His was a national touring company that took opera to the people. Before 1954,

opera in New Zealand was either performed by amateur groups or by overseas

professional touring companies. The idea with the Opera Company was to eventually

put singers on permanent contracts, which eventuated in the early 1960s. Until

then, singers were, paradoxically, often unavailable, despite wanting this

line of work, because they had other jobs. This, in turn, created difficulties

in mounting a season because the availability of singers was often difficult

to coordinate. Nor were production problems confined to that area: the orchestral

scores for The Medium arrived three days before the opening night,

which placed a strain on the orchestra. Nevertheless the show always managed

to go on and a cadre of professional singers took the Opera Company to its

successes in the 1960s. My father always believed that professional opera

could be sustained on the basis of local singing talent and the Opera Company

provided the work that prevented their exodus overseas. Well, not quite. So

good were many of the singers that they were inveigled abroad, but plenty

remained to fill the void.

The New Zealand Opera Company is no more. It folded in 1971 when the government

funding body, the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council, declined to provide further

subsidies. (17) Opera in New Zealand

was then kept alive, if not exactly well, when various people associated with

the Opera Company started their own opera groups. The fact remains that during

the 1960s, the Opera Company was New Zealand's most significant cultural institution,

second only to the National Orchestra. Yet its beginnings were so modest and

its early years so tenuous. The advancement of the Opera Company from The

Telephone to grand opera on the scale of The Consul was a far greater

achievement than maintaining the momentum during the following decade on the

basis of major sponsorships. It prompts the reflection that the mid- to late-1950s

was the pivotal period in New Zealand cultural endeavour. The National Orchestra

and the Alex Lindsay String Orchestra were formed in the 1940s but opera,

ballet and repertory were still on an amateur footing. With the establishment

in the mid-1950s of the Richard and Edith Campions' New Zealand Players, Poul

Gnatt's New Zealand Ballet Company and Donald Munro's New Zealand Opera Company,

the cultural landscape changed irrevocably. These were national touring companies

whose high professional standards laid a solid foundation.

They toured

the rural areas as well as the urban centres, made New Zealand and better

and more interesting place in which to live, and provided culturally-minded

Kiwis something they never believed could possibly eventuate.

In July 2005, the 92-year-old Donald Munro received an Icon Award from the Arts Foundation of New Zealand, which to his mind is a far greater honour than the MBE that was conferred on him in 1960. The Icon Award, as he explained, was decided by his peers rather than by politicians.

footnotes:

(1)Adrienne Simpson, Capital Opera: Wellington's

opera company, 1982-1999 (Wellington: The National Opera of Wellington, 2000),

7.

(2)Edward J. Dent, Mozart's Operas, 2nd ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1947), 21.

(3)There is a useful short chapter in Adrienne Simpson, Opera's Farthest Frontier:

a history of professional opera in New Zealand (Auckland: Reed, 1996), 205-19.

(4)Ashley Brilliant, Want to Reach Your Mind - where is it currently located?

(Santa Barbara, CA: Woodbridge Press, 1994), 78.

(5)Bruce Mason, The End of the Golden Weather:

a voyage into a New Zealand childhood (Wellington: Price Milburn, 1962), 11.

(6)The major documentary sources for this article are the Records of the New

Zealand, Opera Company (especially the Minutes of the Board of Directors),

Alexander (7)Turnbull Library, MS-Group-0061; the Papers of Donald Munro,

Alexander Turnbull Library, MS-Group-0606; and the Department of Internal

Affairs' early files relating to the Opera Company in Archives New Zealand,

IA, W2587, 155/206/729; IA, W2578, 158/206/808. My research notes and taped

interviews relating to the New Zealand Opera Company will eventually be deposited

in the Turnbull Library.

Auckland Star, 15 May 1951.

(8)George Scott Morrison, This is My Story - This is My Song (Wellington:

Steele Roberts, [2004]), 95.

(9) The one occasion when the family performed

together was at St Paul's Cathedral, Wellington, 30 March 1958. My father

sang the part of Jesus in the St Matthew Passion and my mother played the

viola in the accompanying string quintet while my brother and I were boy sopranos

in the choir.

(10) John Mansfield Thomson, Into a New Key: the origins and history of the

Music Federation of New Zealand, 1950-1982 (Wellington: Music Federation of

New Zealand, 1985), 60-62; Adrienne Simpson and Geoffrey Newson, Alex Lindsay:

the man and his orchestra (Christchurch: School of Music, University of Canterbury,

1998), 19-20.

(11)The Auckland CAS's contribution to cultural life is discussed by Peter

Harcourt, A Dramatic Appearance: New Zealand theatre, 1920-1970 (Wellington:

Methuen, 1978), 84-87.

(12) Dominion, 19 October 1954; Evening Post, 19 October 1954. See also Frederick Page, 'Intimate Opera', Landfall, 36 (1954), 349-51; NZ Listener, 5 November 1954, 10.

(13) Newson to Munro, 12 November 1954 (original

in my possession). Part of the letter has come adrift so I have silently restored

what I take to be the missing words.

(14) This is discussed in Philip Norman's upcoming biography of Lilburn, which

will be published later this year by Canterbury University Press.

15) 'Looking Back: the Opera Society, 1954-1979',

Opera News (Wellington), October 1979, 2-4; Roger Wilson, 'The New Zealand

Opera Society', in Adrienne Simpson (ed.) Opera in New Zealand: aspects of

history and performance (Wellington: Witham Press, 1990), 133-41.

(16) 'Intimate Opera in New Zealand', NZ Listener, 8 March 1957, 6.

(17) See Nicholas Tarling, On and Off: opera in Auckland, 1970-2000 (Palmerston

North: Dunmore Press, 2002), ch.2.

DONALD

MUNRO

TIMELINE

1913

Born 10 January, Mosgiel, New

Zealand

Education

East Taieri Primary School

Mosgiel District High School

Otago Boys' High School

King Edward Technical College

1925

Moved to Dunedin, beacme a well known boy soprano

1929-39

These were depression years when permanent employment became almost non-existent. Donald engaged ina variety of jobs, including office clerk, waiter, taxi driver, truck driver and gold miner.

His sports were rugby, rowing and motor bike racing.

He stopped these activities when he began singing lessons, winning many prizes in local competitions and taking part in Operatic Society performances.

1939

Travelled to England and was accepted as a student at the Royal College of Music.

1941

Awarded the Tagore Gold Medal presented each year to the outstanding student at the Royal College of Music.

Won a Leverhulme Scholarship in open competition and the Harry Leslie Singing Prize.

Gave many student recitals and took part in oratorio and opera performances.

Successfully auditioned for the BBC and gave radio recitalsand open performances.

1942

Joined Sadlers Wells Opera and sang as a deputy with Westminster Abbey and St Paul's choirs.

1944-46

Played Faulkland in The Rivals (Sheridan) for the Old Vic Company and took part in oratorio performances in London and the provinces.

Also took part in radio performances for the BBC

1946-47

Studied French vocal repertoire with Pierre Bernac in Paris.

1947-51

Gave four Wigmore Hall Recitals.

Sang in BBC broadcasts of operas, including La Vida Breve (Manuel de Falla) and Les deux journées (Cherubini), both in French under Sie Thomas Beecham.

Also A Village Romeo and Juliet (Delius), also under Beecham, and later recorded for HMV. (Recently re-released as a Naxos CD).

Sang the role of Adonis (Blow) at Ragley Hall, Alcester and the Great Hall, Hampton Court.

1951

Returned to New Zealand and set up a teaching practice in Dunedin.

1952

Moved to Wellington.

1953

Took part in the North Island tour of La Serva Padrona (Pergolesi) directed by Layton Ring for the Auckland CAS.

Sang the role of Prpheus in Orpheus and Euridice (Gluck) for New Plymouth Choral Society.

1954

Founded the New Zealand Opera Company with performances of The Telephone (Menotti) and La Serva Padrona (Pergolesi) in Wellington and Lower Hutt.

1954-1967

During these years the Opera Company developed. Munro mounted several more operas by Menotti, namely The Medium, Amahl and th e Night Visitors and The Consul. The latter was the first venture by the company into a three act opera and for the first time it performed in the Wellington Opera House. It was directed by Richard Campion and conducted by James Robertson.

The following year, in 1958, after touring 47 locations with sgortened versions of The Marriage of Figaro (Mozart), the Company presented the full version in the Wellington Opera House. Frank Ponton directed and John Hopkins conducted. That started our venture into the classical repertoire. The Barber of Seville, Madam Butterfly, Tosca, La Traviata, The Bartered Bride, Cosi fan Tutte, La Boheme, The Magic Flute and Rigoletto followed.

Donald Munro's swan song was touring Porgy and Bess throughout New Zealand and Australia in 1965-66.

After that Donald Munro resigned from the Company and was appointed Senior Lecturer at the Elder Conservatorium of Music, University of Adelaide, as Head of the opera and vocal departments. In the following years he directed several operas including Cosi fan Tutte, The Marriage of Figaro, The Magic Flute and Idomeneo, all by Mozart.

1974

Appointed Associate Dean of Music at the University of Adelaide.

1976-1982

Appointed Dean of Music at the University of Adelaide.

President of the Arts Council of South Australia.

Served on the Arts Grants Advisory Committee of South Australia.

Appointed Deputy Chairman of the Arts Council of Australia (a funding body).

Founded the North Adelaide Music Club.

1982

Retired from the University of Adelaide.

1983

Moved to Sydney and set up a teaching practice.

1989-1993

Lived in Germany and taught singing and coached singers in operatic roles in Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen.

1993-2005

Returned to Sydney and resumed as a singing teacher and opera coach to a diminished degree.

2009

Donald is now resident in Willunga south of Adelaide and is still teaching and enjoying his life to the full.

2012

On Wednesday the 18th of January 2012 Donald Munro passed away peacefully in his sleep in hospital having just turned 99 years of age on the 10th of January.

THE NEW ZEALAND OPERA COMPANY gave many singers and technical staff full time employment. It nurtured resident singers and had little difficulty in launching successful careers overseas. To name some:

Noel Mangin ( Hamburg State Opera and the Bavrian State Opera Munich)

Jon Andrew (Deutsche Oper am Rhein - Düsseldorf - La Scala Milan)

Peter Baillie (Vienna Volksoper)

Mary O'Brien (Europe and USA)

Ronald Maconachie (The Australian Opera)